Data gathered by the St. Louis Regional Freightway indicates that, in recent years, there have been tremendous shifts in what was flowing through the region’s freight network.

From iron ore and steel to soybean and plastics, different commodities have at different times moved by the thousands of tons or slowed to a trickle. But those changes have largely gone unnoticed and occurred without any negative effect on the region’s freight economy because the flexibility of the St. Louis region’s world class freight network allowed it to seamlessly adapt.

“As a global freight hub, it’s only natural large quantities of different commodities flow through the St. Louis region. What’s surprising is the dramatic shifts in the types of commodities moving through the bi-state area in recent years and the origins of some of those commodities,” said Mary Lamie, executive director of the St. Louis Regional Freightway. “No matter what was flowing or where it was flowing from, the region’s freight network accommodated those shifts in the national and global freight environment with ease.”

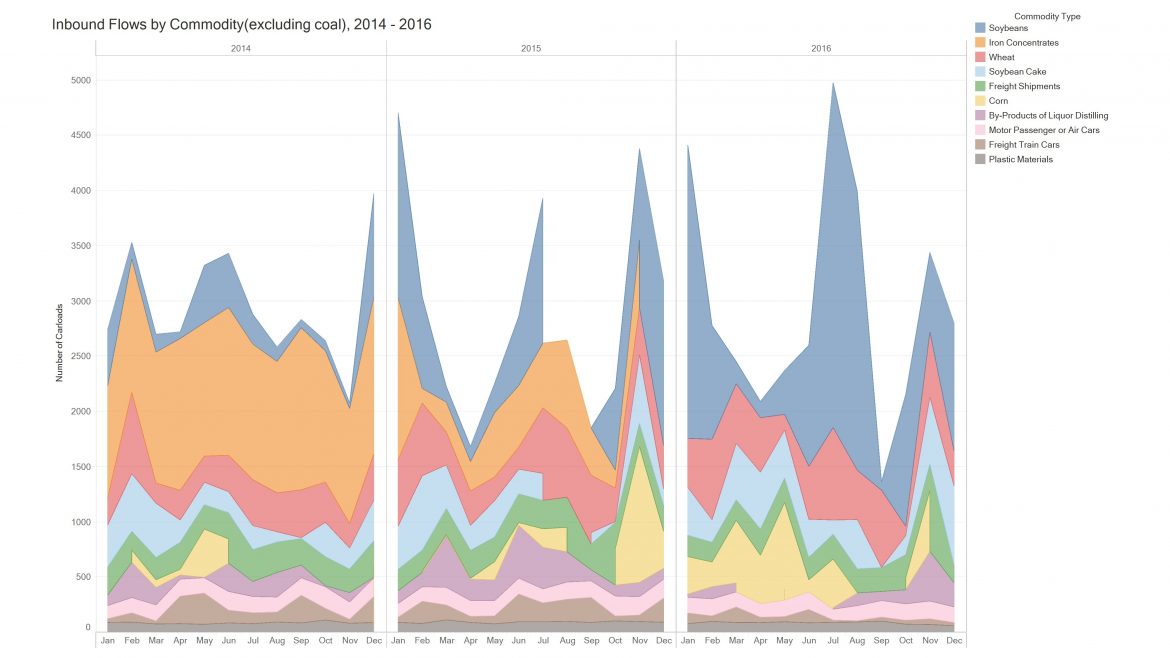

The data reveals some of the biggest shifts were the result of changes in the global steel market in 2014, which caused a slowdown in production at U.S. Steel’s facility in Granite City, Ill. The ultimate idling of the plant in 2015 led to a sharp drop in inbound iron ore flows. This unexpected absence of freight movement had the potential to leave large segments of the region’s freight network underutilized. However, freight and logistics leaders in the area were able to adapt to accommodate a significant increase in carloads of soybeans and other bulk agricultural products that were moving in the region during the same period, ensuring the bi-state area’s freight economy would not be impacted in the face of sudden changes to market conditions.

“Much of the impact on different commodity movements and traffic volumes here originates outside the St. Louis region, because we are one of the nation’s largest freight hubs,” notes Mike McCarthy, president of the Terminal Rail Road Association (TRRA). “National and international shifts that we have felt have been brought about by things such as spikes of crude oil shipments, sand movements for fracking oil and natural gas, natural disasters, as well as the opening and closing of steel production facilities. Just when you think you have it figured out, the game changes.”

The game has changed again now that idled facilities at the steel mill in Granite City have been reactivated. News reports indicate the capacity of the steel facility should once again be almost double what it was in 2014, when the slowdown began. TRRA has recently added 15 jobs and filled a vacant management position to keep up with the increased traffic related to the renewed flow of inbound iron ore and outbound finished steel product.

Meanwhile, the region’s freight network continues to carry large volumes of agriculture commodities, despite the uncertainty resulting from the evolving global trade war and, in part, because of it.

“Due to the dramatic decrease in soybean exports to China, the soybeans produced in states like North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, etc. – that typically feed into Pacific Northwest export terminals in order to be exported to China – needed to find another customer,” says Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soy Transportation Coalition, an organization comprised of soybean boards in 13 states encompassing 85 percent of total U.S. soybean production, along with the American Soybean Association, and the United Soybean Board. “That has resulted in increased volumes being sent to areas like St. Louis, since the Mississippi River to Mississippi Gulf supply chain provides access to a wider array of international customers (Europe, Africa, South America, etc.). How long this continues is very uncertain.”

Freight industry leaders in the St. Louis region remain optimistic the region’s flexible and competitive freight network will continue to be utilized to reach those new international customers for soybeans, while also having the ability to adapt to the unpredictability of the marketplace. Today, a 15-mile stretch of the Mississippi River in the bi-state area is known as the Ag Coast of America – delivering the highest level of grain barge handling capacity anywhere along the river, with 15 barge-loading facilities, unit-train access, and a large concentration of available ports and river terminals. David Jump, president of Cahokia, Illinois-based American Milling, believes the grain flows through the region will remain strong due to the inherent benefits and efficiencies the Ag Coast provides.

“The railroads like the fast cycle time, which gives them better utility on their assets, and the barge lines love turning their boats in St. Louis and returning quickly to New Orleans,” said Jump. “The barge freight rates reflect that.”

According to Jump, there has been consolidation in the river transportation industry over the last 20 years, and barge lines are becoming more streamlined by focusing on efficiency. Railroads have offered cheaper rates to large barge-loading facilities that can turn unit trains — carrying 110 to 125 railcars of grain and agricultural product — in hours.

“Barge loading and unloading capacity has expanded in the St. Louis area to take advantage of these train rates and barge freight rate adjustments,” Jump said.

For now, the region’s freight network clearly has the capacity to handle the evolving flows, and amidst the excitement that the steel plant is back up and running, there is confidence the region’s freight network will continue to respond well.

“Generally speaking, there’s transportation capacity in St. Louis,” said Matt Freix, regional vice president, DNJ Intermodal Services. “We still have long term infrastructure needs that should be addressed, but I don’t think the renewed activity at the Granite City Works is going to be a tipping point. It’s just a benefit to the region.”